LP: Your childhood, salmon fishing and a certain part of the lower mainland where you grew up play an integral role in most of your writing. Can you fill us in on that background?

TB: Re; my background: I was born in Vancouver and immediately taken under the Fraser (via the Deas Tunnel) to Ladner – a salmon-like little journey appropriate for someone who’d grow up to be so involved with that magical species. I had an idyllic childhood at the mouth of North America’s wildest river, a Huck Finn childhood of raftings and roamings, except, unlike Huck, I had loving and supportive parents! What can I say? I was very fortunate; children weren’t then supervised every second of the day, my family worked in the salmon fishery, and so I spent a lot of time on my own in the

outdoors. Everything I write comes out of the sense of awe I drank in daily

as a boy.

LP: When you finished high school you went away to university, got your degree, and then came back to the fishing industry for a fair number of years. Where and when did the urge to write begin?

TB: Re: the urge to write: It was always there. In grade one, I remember answering that infamous question “What do you want to be when you grow up?” with “A writer.” Why? Who knows?

LP: Did you leave fishing simply because it was a dying industry or did the writing take over as your primary focus?

TB: As much as I appreciated the work of salmon fishing, I was never entirely at ease in the culture. In fact, I was only an appendage to it, as my older brother, Rick, rented the boats and made the decisions. I got my hands wet and bloody, right enough, but the stresses were mostly his. All through the 80s, I was focussed on the apprentice work of the poet and novelist (ie, reading a lot and writing a lot, most of the latter material being bad, of course)

LP: You now live in Edmonton. How did you end up there?

TB: Long story. To be brief, I moved to be with the woman who is now my wife. Funny thing is, I have very deep roots in Edmonton – my great-grandparents moved here from Ontario in 1905 and my father was born here in 1923. I’m only now beginning to explore these roots in my work.

LP: Is it a challenge to maintain your ties, creatively, to the west coast while living on the prairies?

TB: No challenge at all. But perhaps that’s because I visit the coast at least twice a year (for several weeks at a time) to see my family. In any case, Edmonton, like my hometown, has a river running through it. That helps.

LP: You have written poems and a novel set in Alberta but, if anything your Alberta focus seems more on the Badlands area rather than Edmonton. Why, what appeals about an area that is so different from your west coast home?

TB: The badlands reminded me very much of the west coast circa 1970 because of all the darkness and silence (the title of my poetry collection that contains several badlands poems). I’d sit on the porch at night in the Red Deer River Valley and feel that I was standing on the deck of a Fraser River gillnetter – the same sense of mystery and awe, the same exhilarating closeness to the source of things. But I should point out that Edmonton is becoming more of a focus. I’m currently writing a full-length collection of prose and poetry that investigates my family’s pioneering role as Edmonton

beekeepers.

LP: Even when you do write about Edmonton, and I’m thinking here of the poem A Cup Of Coffee In Solitude which starts with the line –January in Edmonton – later you write -A car passes on the muffled road, spawning salmon slow. Do you think that earlier life will always infuse your work?

TB: Yes. as Flannery O’Connor said, “Who ever’s been through childhood has enough material for several lifetimes.”

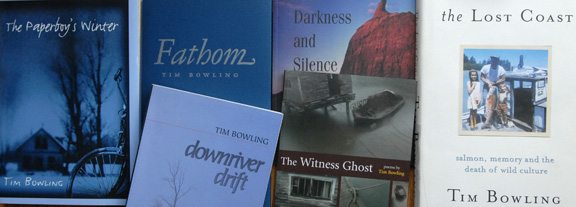

LP: Your last book, the memoir The Lost Coast talks about growing up in Ladner on the Fraser River, your family and fishing. Your two novels Downriver Drift and The Paperboy’s Winter are set in that area and deal with the land/riverscape, families and fishing. Most novelists do mine their own lives but are careful to point out that the stories are fiction, only loosely based on real life. You sort of undermine that in the memoir by telling the real life stories that parts of the novels are based on. Any thoughts on that?

TB: Hmm, I wasn’t aware that most writers are careful to make the point re: fiction vs autobiography. It’s an odd thing to worry about. Good writing is good writing. Besides, as anyone who’s ever written a memoir will tell you, memory plays a lot of tricks with reality. Even when I’m writing straight out of my own life, I’m fictionalizing much of the time. The key point, of course, is that the writer must transmute lived experience into meaningful art.

LP. In the acknowledgments for your novel Downriver Drift one of the people you thank is writer Jack Hodgins. Hodgins is noted for the depiction of Vancouver Island life, or at least a certain Vancouver Island life, in his novels. Did you ever talk about the details and the sense of place in writing?

TB: Jack Hodgins actually edited Downriver Drift. And what a gift that was for a beginning novelist! Jack is a superb editor, sensitive to every little nuance of prose style and critical in the most encouraging way. I don’t recall that we talked much about the sense of place, likely because it’s not something either of us would really consider – we just write out

of the worlds we came from, without doubt, without apology. Most of our editing discussions were more technical.

LP: You have two new books of poetry out this fall. Nightwood Editions is publishing The Book Collector and Other Poems. What can you tell us about this book?

TB: Many of the poems in The Book Collector were written when I lived in Gibsons from 2004-2006, so there’s a Sunshine Coast flavour to many of the poems. Briefly, the book contains nearly 40 poems touching on a wide range of subjects, from books and art to soccer and salmon. I hope the metaphors are memorable; I put a lot of faith in them.

LP; Your other book of poetry coming out is from Gaspereau Press, the magnificently titled Refrain For Rental Boat #4. It is a 12 page , limited edition book priced at $160. Gaspereau is noted for their beautiful regular editions so I’m assuming this will be something quite special. What’s the story behind this book?

TB: Refrain for Rental Boat #4 was removed from my 2006 book, FATHOM, because the editor and I didn’t think that it fit tonally with the other poems. Then I read the poem after publication, at one of Gaspereau’s annual parties in Kentville, NS, and Andrew Steeves, who liked it a lot, wondered why it hadn’t been included in FATHOM. After I told him, he said he’d like to do the poem as a limited edition. There’s only been four copies finished to this point, three of which I have. 45 copies will be made in total, and I believe the cost is $100.

LP: Earlier this year you were one of the winners of the Guggenheim Prize, the only Canadian winner. It’s certainly an honour to win and the prize money attached would be welcome too. This was your first attempt at the Guggenheim, did you have any expectations of being chosen for the award?

TB: No serious expectations, but I never apply for things if I don’t think I have a chance. And the Guggenheim is an award whose criteria seemed a good fit for me, in that the Foundation wants to fund those with a solid publishing record who seem likely to continue publishing.

LP: You are a prolific writer, have published books of poetry, novels, a memoir and edited a book of interviews with poets. You won a number of awards for that writing as well and yet you seem to fly under the radar as far as the press goes. It’s difficult to find interviews with you or even articles about you. It was surprising that even for the Guggenheim, it appears only the National Post did a stand alone interview with you. Is that a deliberate strategy on your part? Do you avoid media coverage? If not why do you think you get overlooked.

TB: I don’t exactly avoid the media, but I certainly don’t seek them out either. Newspapers, TV, magazines (even, gasp, websites) rarely pay for a writer’s time, and, given my busy domestic and writing schedule, I can’t afford to work for nothing. Usually, though, I’ll do interviews when I have a new book out. All things considered, I’m a pretty amenable type.

LP: In The Lost Coast you make the point that you don’t live in the past, that you type on a computer, communicate with your editors over the internet but a certain yearning for the past and maybe even some anger at losing that past seems to be part of your writing. Do you think so?

TB: Absolutely. But I’m not stupid about the past either. Of course there’s no Golden Age. On the other hand, there’s almost no fishing industry anymore, the growth of the farmed fish business moves along in happy tandem with the growth of neo-conservative conformity, and every year moves me closer towards death – yearning and anger seem reasonable enough.

LP. What’s your next project?

TB: I’ve just finished a new non-fiction ms. which is entirely different from THE LOST COAST. In fact, the whole story takes place in Edmonton, mostly in a library, and deals with my interest in a little-known American poet named Weldon Kees who jumped off the Golden Gate Bridge in 1955. I’m also doing preliminary research for a new novel set on the Fraser River and in the American South in the mid and late nineteenth century.

LP: When you were working as a fisherman, you were also writing poetry, correct? Was your writing something that ever came up with other fishermen and if so, what was the reaction?

TB: No, my writing never came up, mostly because I never brought it up. But then, I wouldn’t want to talk about poetry with most graduate students in English Literature either! In fact, my salmon fishing poems, all my poems set on the Fraser, have gone over very well with Ladner folks.

LP: In our memoir you indicate your dissatisfaction with the school system so I’m assuming your kids are home schooled? How does that affect your writing, what special allowances do you have to make to your writing schedule?

TB: Yes, my kids are home schooled. Not only do I think school is one of the great brainwashers into North American culture and capitalism (a culture not entirely repellent, of course, but one that could be resisted a bit more seriously), I just don’t want not to see my children for six hours a day, five days a week. I mean, I really enjoy them. I’m selfish that way. On average, I suppose I write two hours a day and parent the rest. This is a tricky schedule when I get deep into a book, but hell, children are more important than books.